My Life with the XK-E - Part 1

by George Anderson, ESEP

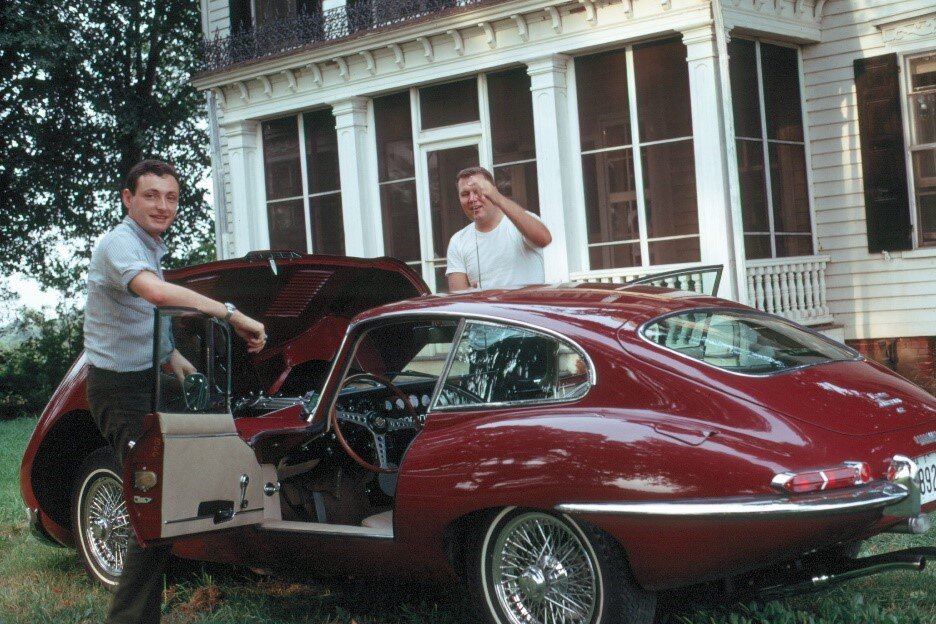

Figure 1. Author with his new 1968 Jaguar XK-E

I bought my new Jaguar XK-E fixed head coupe (FHD) at Reedman Auto Group in Langhorne, PA in July 1968. It was painted opalescent maroon and included air conditioning, chrome wire wheels and Dunlop racing tires. It was both a beautiful car and a significant advance in mechanical design that is still universally admired. It commands big prices in the restoration market today and there is a cottage industry of pundits, collectors, and restorers promoting the glories of the XK-E. [1]

You can go for a virtual ride in an XK-E on YouTube, listen to Jay Leno lecture on the finer points of the car’s design history and view restored examples for sale with prices ranging from $50,000 to $120,000.

I would like to share my experiences with the XK-E and perhaps cover some aspects that are missing from contemporary reviews. Many of these reviews and driver impressions are years away from the original car that was delivered to me from Coventry, England in 1968.

I owned my XK-E for 13 years and drove it as my primary car including long trips and daily commutes. It was unquestionably the best car that I have owned for experiencing pure driving pleasure. For me, the car also proved to be very reliable when compared to other high-performance cars of the period. All the Jaguar cars at that time were high performance and reflected innovations based on their racing heritage.

Owning the XK-E changed my life in several ways. Within weeks of taking delivery of the car I realized that I would have to do most of the maintenance if the car were to survive. Mechanics at the dealership and elsewhere appeared to have never seen a Jaguar. Several mechanics seemed to take things apart just for curiosity and I was shocked to observe a service station attendant on the Pennsylvania Turnpike attempting to remove the chrome plated oil dip stick with a pair of vice grips. After that, no mechanic or station attendant was allowed near the car. A new set of Sears tools including socket wrenches was my first support purchase. Later there would be special tools unique to the XK-E but these were far in the future and well into my learning curve with the XK-E.

Making a commitment to be your own mechanic is not an easy decision, but it changed part of my perspective in life and caused me to employ some of the systems engineering concepts that I used in my day job. To say the car was a systems masterpiece in its integration and detail design is merely echoing others but there was not a day that I did not enjoy learning more about “the inner workings and hidden mechanisms”. [2] The car like so many others had a personality with strengths and weaknesses, both of which I came to appreciate. Notwithstanding, there was no temptation to add, modify or tweak any aspect of its mechanicals or appearance. The reason was probably that it resembled the biological architecture of its namesake in both concept and execution. In 1968 one did not mess with biomimicry done well. (Figure 2.)

Most systems engineers are accustomed to spending much of their efforts in the Development phase of the Systems Engineering life cycle. In my case, the responsibilities began at the end of the production stage and proceeded through Operations to the Disposal phase.

Figure 2. Hot August day at the farm in New Jersey. Note the twin chrome exhausts.

My participation in the car’s life cycle can be covered in four parts:

Validation-The car’s delivery specifications and translation into customer expectations

Operations-The driving experience

Maintenance & Logistics-Becoming a systems expert and establishing logistics support

Disposal-Identifying a new owner that has the means and motivation to preserve the vehicle in running condition. No barn storage schemes.[3]

Part 1 of this article will cover Verification and Operations. Separately, Part 2 will cover Maintenance, Logistics, and Disposal.[4]

Verification- Were the customer’s needs and expectations met?

My 1968 Jaguar XK-E Series 2.0 Fixed Head Coupe came to me equipped with chromed wire wheels, air conditioning, Dunlop white sidewall racing tires and knock off wheel hubs and a single ignition key. I guess it was never imagined that this was anything but a one driver car. The six-cylinder, 4.2-liter engine of approximately 265 HP drove a four-speed manual transmission connected to a limited slip rear differential. Steering was rack and pinion type with no damping. The all-wheel disc brakes and radial tires where ahead of their time in the U.S. as was the front and rear independent suspension.

Figure 3. Ready for Takeoff. Note the Shifter for the All Synchromesh Four Speed Manual Transmission.

What did I expect when I bought this car? I expected to have a sports car that looked better than the then popular trio of competitors, namely the Corvette, Porsche 911, and Mercedes 280SL. I expected it to be fast, accelerate rapidly and handle well. I liked the interior design. It resembled a fighter aircraft cockpit with the professional looking dashboard filled with the uniformly round performance gages. It was also cramped. Like many British cars of the era, you sat beside, not behind the transmission. (Figure 3.) During extended driving at high speeds the transmission heat was noticeable in the cabin. Not stifling but you knew that the car was alive.

I wasted no time checking on the performance. I clocked the car out at a top speed of 125 at which point the ignition coil failed with an alarming bang. It was replaced and I never went that fast again.

Handling and feel were excellent, and the sitting position was comfortable and supporting in high performance turns. You were sitting down between the high door rail and the transmission housing, so you had extremely limited room to move sideways. The ergonomics of operating the accelerator, clutch and brake were awkward by normal standards but you adapted to it quickly. The space would not accommodate unusually tall or short individuals comfortably as was the case in many fighter aircraft (Figure 4) where height restrictions were enforced. [5] The accelerator was firm partly due to the series of articulated rods that connected to the carburetors located on the right side of the engine. The clutch was hydraulically operated and was equally stiff. Finally, the brake pedal had a positive and easy action due to a larger than normal vacuum booster. Stopping power was exceptionally good.

Figure 4 Restored Spitfire Cockpit showing cramped interior and classic round dial instruments.

Starting this car was always a great experience. Apply manual choke engage the starter and it roared to life unfailingly. The distinctive throaty sound of the engine as it accelerated was always audible to both the occupants and by- standers. Its sound spectrum was no accident as the XK-E had dual mufflers followed by special chrome plated resonators mounted below the center rear body.

There was a distinctive wood steering wheel that suggested the use of driving gloves to avoid disturbing the varnish.

Overall, my validation observations and tests were conclusive. How could anybody not like this car!

Operations- Were there comprehensive operating instructions and were they implemented?

The cars operating instructions were minimal. No special care was needed beyond the normal inspections and recurring service. This included oil changes at 1000 miles with a new oil filter every other oil change.

Brake pads and disc wear was checked every 6 months and brake fluid was flushed every two years.

The front wire wheels needed static and dynamic balancing every six months to a year to avoid excessive vibration in the steering wheel. This was due to tread wear. [6]

Driving in ice and snow and salt treated roads were discouraged, and frequent cleaning of the body was recommended to remove dirt and salt.

The two Zenith-Stromberg carburetors required topping off with a small amount of lubricating oil in the damper assembly every time the engine oil was changed. As I remember, a lack of oil caused the carburetors to run lean during acceleration. Carburetors during this period were treated as complex, finicky and suspected to be the root of many ills. Whole books were written on the details of these carburetors and I read them with great concern. Despite all fears, I had no problems with mine and they consistently performed well.

Figure 5. Crossing the Continental Divide over the Loveland Pass, July 1972

A common complaint of English sports cars is frequent overheating. This car had twin electric fans installed behind the radiator and the engine never to my knowledge overheated even when I drove in desert heat with the air conditioner on or climbed over the Continental Divide in Colorado. We crossed over the Loveland Pass at an elevation of 11,990 ft. traveling eastbound. (Figure 5.)

The octane requirement at the time straddled the limit between regular and high test. While the engine clearly needed high test for high rpm operation, in normal driving I never got near the limit where the engine would ping. I used regular gas unless I had a high-altitude drive or a long trip at higher speeds. It also is true that unleaded fuel was still in use and inhibited both pinging and exhaust valve burning/erosion.

Spark Plug fouling. High performance engines are supposed to foul plugs during extended idling. At first, I worried about this and later realized that it was a chimera. I used the same spark plugs and rarely cleaned them during the last five years of operation. The reason will be explained in the Maintenance process discussion in part 2.

Overall, I was able to accomplish the operational instructions without any difficulties and drove the car extensively in a variety of climate extremes. We went to California from Ohio, vacationed in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, and drove from New Jersey to Montgomery, Alabama and back. All these trips had no breakdowns or failures- not even a burned-out lightbulb. I thought that the reason for so many stories of unreliability was somehow related to the mechanic problems experienced earlier. Certainly, some XK-E’s were treated badly by repair shops but as time went on, I found that there were better mechanics who often provided me with good advice.

Figure 6. The real thing! Unencumbered with headrests, a check engine light, an engine computer, airbags, antilock brakes, All Wheel Drive or advanced smog controls. It did have class, performance and style.

I always felt that the mystification of the XK-E was a huge barrier to good operations. By any analysis, the engine and drive train were bullet proof and except for poor quality control of many of the Lucas [7] electric parts such as ignition coils, nothing was likely to fail during routine driving.

Nevertheless, apocryphal stories abounded about blown head gaskets, bad carburetors, burned valves and engine overheating. I heard these stories while I refueled at many gas stations over the years. Apparently, these car enthusiasts considered it a miracle to see my XK-E starting up and moving off under its own power.

This is the end of my coverage of the XK-E operations phase. Operating instructions were followed, and I performed all the routine inspections and service. There were lessons learned but the real challenges will be covered in the Maintenance phase coming in part 2.

There, I will present my experience pulling the engine, rebuilding wire wheels, replacing the timing chain sprocket, and other significant maintenance events. Logistics topics include getting parts from South Africa, replacing fuel line fittings and my apology to the parts store clerk who taught me about British Whitworth threads.

Look for this if you enjoy complexity as described by a systems engineer. In the meantime, consider taking a moment to read an evaluation of the 1961 Jaguar XK-E by the Magazine Car & Driver originally published in the 1960’s. Please note that there are some differences between my 1968 model and the earlier 1961.

[1] The car was marketed in the US as the XK-E but the British nomenclature was E type. My car displayed chrome lettering on the rear hatch back that read: “E-Type Jaguar 4.2 “. The 4.2 number referred to the engine displacement in liters.

[2] Naval Academy Plebe response: “I am greatly embarrassed and deeply chagrined that due to unforeseen circumstances beyond my control, the inner workings and hidden mechanisms of my chronometer are in such in in-accord with the great sidereal movement with which time is generally reckoned that I cannot with any degree of accuracy state the correct time. But without fear of being too greatly in error, I will state that it is about....”

[3] Many classic cars including the Jaguar XK-E have been found deteriorating in long term storage. I can’t help but feel that this is mainly due to the unwillingness of owners to pay large repair and refurbishment costs as the car exceeds 15 to 20 years old. This life model is generally better than most current production cars who may be not economical to repair after ten years on the road.

[4] The INCOSE Handbook and the ISO/IEC 15288 standard identifies the major life cycle stages as: Development, Production, Utilization, Support, and Retirement. These have been decomposed and tailored to reflect just the owner’s responsibilities.

[5] Previous USAF pilot requirements. Pilots much reach a standing height of 64 inches to 77 inches—5 feet, 4 inches to 6 feet, 6 inches—with a sitting height of 34-40 inches.

[6] The Dunlop racing tires were the best tires for holding the road in curves and wet roads but lasted only a year (12,000mi) of normal driving, so they were soon changed out for 40,000 mi. Bridgestones.

[7] As the hackneyed joke goes: Why do the British have warm beer? Because they have Lucas refrigerators. Lucas is also known as the prince of darkness due to its lighting products.